Over the past month, I have been participating in an “Inculturation Course” at Rosebank Methodist Church. Every Tuesday evening from 7-9pm, a group of church and community members have gathered to discuss South African history, and the lessons, legacies, and personal responsibility we draw from it. We have also talked a lot about South Africa today and the challenges that the country is facing, but also the hope and the faith that people have in their nation, hope which is largely inspired by the incredible leaders and examples who have come before. For me, attending these classes was like being inside of oral history, as I was surrounded by individuals who, in many different ways, and from many different positions, lived inside the history that I have only ever read about. Together, their perspectives built upon and reinforced one another’s. Within the group there was:

- A Methodist minister (my minister) who was very involved in the anti-apartheid struggle and the African National Congress (he was asked on multiple occasions to serve as a member of parliament by the ANC, and each time turned them down).

- The wife of a late Methodist minister who fought against apartheid “before it was popular” and worked to build bridges between the white and black Methodist churches who grew up within the struggle.

- The son of one of Mandela’s wardens on Robben Island.

- An Afrikaans woman who was ashamed to speak her mother tongue until 1994, as it was the “language of the oppressor.”

- The daughter of a member of the Black Sash, a woman’s organization that fought for equal rights.

- Many “Born Frees,” South African youth born after 1994, who never knew apartheid.

- Myself (from the US) and Saviour (from Ghana), the only two foreigners in the group.

- And many others, of all colors, generations, and backgrounds.

Each session had a different topic: the first was on Steve Biko and Donald Woods (the white liberal journalist who became Biko’s dear friend and who helped expose his brutal murder at the hands of the apartheid state to the world; if you have never seen it, go watch the film Cry Freedom), and the Black Consciousness movement; the second was on SASO and NUSAS, the university student organizations that became hotbeds of the liberation movement; the third was on Robert Sobukwe (the founder of the Pan Africanist Congress, a black nationalist movement critical of the ANC’s non-racialism, and prison-mate of Mandela’s on Robben Island) and Beyers Naudé (an Afrikaner cleric who became a leading anti-apartheid activist, and who was regarded as a betrayer of his own people); and the final course was on Nelson Rolihlala Mandela, better known by his clan name, Madiba. Reverend Otto led the class, each of which was broken up into two parts, the first was a historical overview (with much input and addition from those sitting around the circle), and in the second part we were broken up into small groups, to discuss what we could learn from the heroes we were discussing, and how we could incorporate their legacies and values into the struggles of contemporary South Africa.

It would be impossible to convey everything that I learned in these sessions here, but I want to share a few notable moments and overriding themes:

- BOTH black and white South Africans fought during the anti-apartheid struggle, both black and white were imprisoned on Robben Island, and both were killed for their beliefs (“black” here holding its more expansive political meaning, encompassing all who are non-white: in the South African context, largely black, coloured, and Indian). One of the primary messages that Otto wanted to get across in these classes was the reality and the beautiful aspiration that is expressed in the Freedom Charter: “South Africa belongs to all those who live in it.” Much of the racial division that is coming up today is a product of a forgetfulness of this shared struggle and shared legacy. Indeed, many of the Born Frees in the class were surprised to learn just how much white people were involved in the anti-apartheid struggle, to the point of being ostracized from their communities as traitors, and losing their lives. Non-racialism is a tenant on which the new South Africa was built, and one to which it must tenaciously and passionately hold. Rosebank Methodist, both in the creating of spaces such as this, and in the incredible diversity of its community, is trying to actualize this value in its own reality.

- The old guard of the liberation struggle was made up of disciplined men and women who held themselves to high standards with integrity. Today, many of the struggles that South Africa is facing are a product of, or exacerbated by, corruption and selfishness on the part of the leaders in whom the country puts its faith. If the nation is to overcome its daunting obstacles (poverty, HIV/AIDS, a crisis of education, sexual and other violence, crime, and much more, but all interconnected), its leaders need to readopt the discipline that their predecessors had. During one of the classes, someone asked “Why? Why has corruption taken over?” A young man offered a poignant and compassionate response: when you have a hungry dog straining on a leash, thirsting for its freedom, and you let it go, it will go wild for all of the things from which it (and its family) had been deprived, with no one to hold it accountable. We must hold a demand for accountability in balance with this compassion and understanding.

- When Nelson Mandela’s mother took him to be baptized, the priest asked her for her son’s Christian name, and she said “Rolihlala.” The priest said absolutely not and gave him the name Nelson, thinking that Rolihlala would be too much for most people to pronounce (at this point in Otto’s account, most of the class died laughing). However, Mandela’s mother could sense what was in her son’s future, for “Rolihlala,” which became his middle name, signifies “the one who pulls a big crowd.”

- During the anti-apartheid struggle the church (a combined ecumenical coalition of communities of faith) held the mantle of moral consciousness, and now it needs to take it back up. Desmond Tutu is serving as the moral consciousness of South Africa in many ways, and he is tired. He needs backup.

I feel so incredibly blessed to have found my way into this community and space of fellowship, because the telling and sharing of true and nuanced history, and the striving to create a nonracial community is a powerful form of fellowship, and one which South Africans have been pursuing for a very long time. I was clearly an outsider to this space in many ways, but I was welcomed with open arms, and I cannot imagine a more powerful and real way for me to learn about the history and identity of the country in which I now find myself. For many reasons, I think these were important lessons for me to learn within a community of faith. The faith that the people surrounding me had was actualized in their sense of community – in such an intensely divided place as South Africa, they have something much more powerful that unites them – and in the hope and tenacity with which they confront the realities that surround them. Despite the challenges and difficulties, they have a faith that their nation will pull through them. This is not a faith born of naiveté (the ignorance or misunderstanding that optimism is often attributed to by those who do not truly understand it), but one born out of a real and deep understanding of where they come from, a compassion and respect for those around them (all of whom to which South Africa belongs), and a bottomless font of motivation and determination to continue in the direction in which they are going.

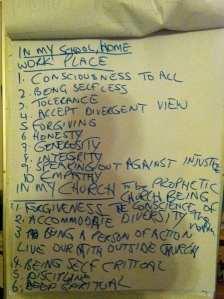

Things we can learn from Mandela

Miscellaneous:

English midterm – Slavoj Zizek, hedonist consumerism and jouissance

Book #5

Thanks, Kyra, for sharing all you are learning about social activism and the politics of inclusion in South Africa.